What is inflation and why is everything suddenly more expensive?

By Tom Watson

Inflation. It's that word we keep hearing about and the topic that just won't go away, especially in the context of rising living costs which the majority of Australians have been experiencing so far throughout 2022.

But what exactly is inflation? Why are things more getting more expensive? And what, if anything, does inflation have to do with interest rates or even wages?

Read on as we tackle some of the basic questions around inflation with the help of two economists.

What is inflation?

Ever wondered why lollies or ice cream seemed way cheaper when you were a kid? You're not misremembering anything, they probably were, but in the time since they've been subject to inflation.

Take the price of milk for example. In 1970 you could expect to pay roughly 19 cents for a litre of milk, but fast-forward 50 years and that price is around $2 at its cheapest, and likely a dollar or two more.

"Inflation is basically a persistent and gentle rise in the cost of living through time," says the head of investment strategy and chief economist at AMP, Shane Oliver.

"A one-off rise in petrol prices or a one-off rise in lettuce prices doesn't cut it though, it has to be a persistent, generalised increase."

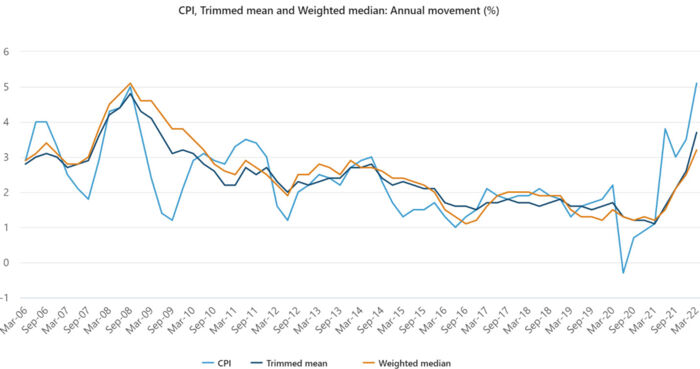

One way to measure the changing prices of various goods and services over time is via the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is released on a quarterly basis by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The index covers a typical basket of goods and services that would be consumed by most households, including food, alcohol, clothing, transport, housing, education, financial services and more.

As the graph above shows, CPI (also called headline inflation) fluctuates over time, but the most recent update showed that CPI rose by 5.1% in the 12 months to March 2022 - the largest annual increase since the Global Financial Crisis.

While it does cover most of the goods and services Australian households typically use, it's worth noting that CPI doesn't track inflation in all parts of the economy though. In fact, the Australian Bureau of Statistics uses a number of other indexes to track inflation too.

Why is the price of everything going up?

Now that you've got an idea of what inflation is and how it's tracked, your next question might be 'why has everything suddenly become so much more expensive than it was?'.

So far this year motorists have watched petrol prices shoot up above $2.20/L and even $2.30/L in some areas; shoppers have seen the cost of groceries, especially fresh fruit and vegetables, increase to the point where iceberg lettuces were being sold at over $10 a head; and most recently, households in New South Wales, south-east Queensland and South Australia have been warned that energy prices will likely rise by 1.7% and 8.2% (and that's above inflation).

While the pandemic is by no means the only factor causing the recent price increases in so many goods and services, it is still playing havoc with the manufacture and distribution of goods around the world, which has a flow-on effect to Australia.

"It's mostly supply related and the key driver of that is the distortions caused by the pandemic, which has disrupted supply chains globally. The pandemic has also led to a big increase in demand for goods relative to services," says Oliver.

"The war in Ukraine and the floods have really just added to the supply-side problems. Obviously, the war has disrupted the supply of oil, energy and various other commodities, and the floods have disrupted the supply of fruit and vegetables in particular."

In turn, that diminished supply of various goods, or energy, or fruit and vegetables mean that there's more demand (relatively). And more demand means that suppliers or businesses tend to increase their prices: either out of necessity to cover their costs, or to simply increase their profits.

How will higher interest rates help dampen inflation?

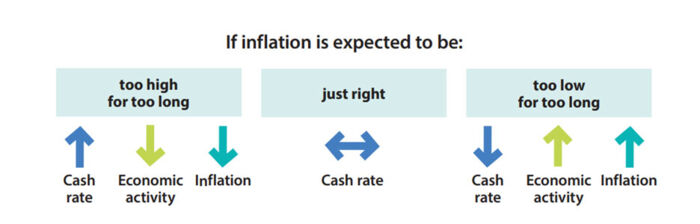

In the past three months, the Reserve Bank has made three consecutive hikes to the official cash rate: 25 basis points in May, 50 basis points in June and another 50 basis points in July. As a result, the cash rate has shot up from 0.10% to 1.35%.

Now, the RBA hasn't been lifting rates for the fun of it, or to make mortgage holders' lives more difficult.

Governor Philip Lowe has made it clear in his monetary policy decision statements that the central bank is aiming to use the cash rate to help drive down inflation back to an ideal range of between 2-3%.

So how does that actually work?

The simple answer is that by saddling people with more expensive debt (via increases to the interest rates they're paying on their home loans, personal loans, business loans etc.) they will be less likely to go out and spend money.

"Basically, it helps slow inflation by making a significant proportion of people poorer," says senior economist at The Australia Institute, Matt Grudnoff.

"About a third of households have a mortgage, so if you have to pay more interest on your mortgage, then your ability to spend on everything else effectively goes down. Then if you spend less money on everything else, demand for everything else goes down and firms suddenly aren't able to put up their prices as much because they're having trouble selling their stuff."

As Grudnoff explains, it's a fine balance though.

"Of course, if there's less demand for stuff that also means that less people will be needed to make that stuff, so what we actually see is a fall in employment and a rise in unemployment."

Will wage rises really drive inflation up?

The thing about inflation is that it can erode people's purchasing power over time - that is, unless incomes keep pace. Simply put, if the price of a litre of milk were to keep rising at a faster rate than the wage you are earning to help pay for it, you would find it harder and harder to afford it over time.

But one of the hot topics at present, given the relatively high rate of inflation we're experiencing, is that a rise in workers' wages would only give people more money to spend, which would then lead to an increase in demand and, as a result, higher prices.

So, the big question is, does wage growth lead to inflation?

"Economists would say that unless the average increase in wages is higher than the increase in prices plus productivity, then no, it won't," Grudnoff says.

"If inflation is 5% and productivity is 1% then workers can get up to 6% wage growth every year, on average, without it adding to inflation - that is, it won't push inflation even higher than 5%."

That's not to say that wage growth hasn't had an impact on inflation in the past though - the oil crisis and wage-price spiral of the 1970s, where wages and prices pushed each other higher and higher, being one notable example.

But as Grudnoff explains, the general decline in the ability of employees to command higher wages means that a situation like that is unlikely at present.

"What we've seen over the last decade in Australia is that the total amount of income going to profits is at a record high and the total amount of income going to wages is at record lows.

"What we're not seeing is that power on the employee side, and we haven't seen it since about 2012-13. There seems to have been a real change in the power relations between employers and employees, where workers are struggling to demand higher wages, even when unemployment is at historic lows.

"The official data from the ABS still shows wages growth at that sort of anaemic, pre-pandemic level of about 2-2.5% which is well below the long-term average of about 3.5%."

Now, that's just a brief dive into inflation, but if you're interested in similar topics then you may enjoy learning about what stagflation is, and whether it's making a comeback or you may find it useful to check out our beginner's guide to rising cash rates and your home loan.

Get stories like this in our newsletters.