How to understand finance news

By David Thornton

Finance news is a daily feature in many living rooms, alongside the sport and weather.

For the more financially literate, it's a handy overview of market movements and economic developments. For others, it's complete gobbledygook best dealt with by reaching for the mute button.

But it doesn't have to be that way. Here's a quick breakdown of what finance news is all about.

Don't freak out

The stockmarket and the economy are not the same thing. The stockmarket is just one of the markets that make up the economy, like the housing market.

While the stockmarket is considered a leading indicator of the economy, the two don't share a dependable relationship. You shouldn't extrapolate what the economy will do tomorrow from what the market does today.

Case in point: in 1987 the US stockmarket crashed 23% in a single day, yet the US economy didn't seem to miss a beat - its economy still grew from the previous year, and went up again the year thereafter. In 2007-2008, however, the sub-prime crisis saw the economy and stockmarket fall in lockstep.

Josh Brown from Ritholtz Wealth Management has a useful way of explaining it.

Picture a person (the economy) walking a dog (the stockmarket) through a park. They both go in the same direction, linked by a leash. The man walks at a steady pace most of the time.

The dog, on the other hand, might be darting all over the place. The dog's short-term movement, be it calm or volatile, is usually of little long-term consequence. But if the dog stops because nature calls, or bolts in chase of another dog, the owner might have to make a correction, stopping for a time or changing direction.

The short of it is this: don't expect a bad day for markets to turn into an economic downturn. Doing so could lead to impulsive investment decisions that can harm long-term investing.

Index breakdown

Financial news always touches on indices - baskets of stocks that aim to provide snapshots of different markets.

Some are more relevant than others. Take the US. Its S&P 500 tracks the 500 largest companies across multiple US stockmarkets, so it's a good barometer. The Dow Jones, on the other hand, is fairly antiquated - full of blue-chip stocks of yesteryear and only includes one FAANG tech stock (Apple).

This is a problem, given the highs the US market is currently experiencing is thanks largely to them.

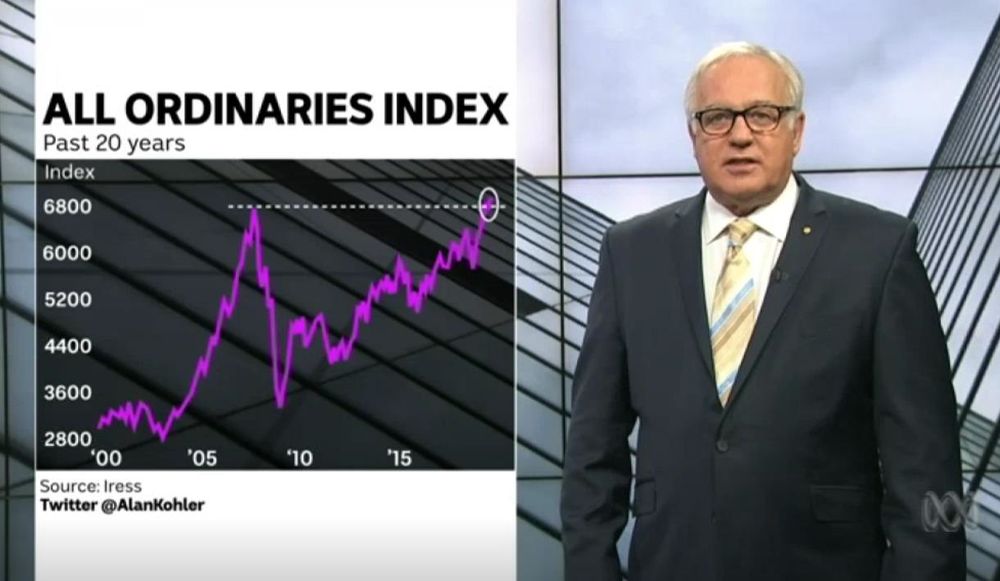

Here at home, two indices stand above the rest: The All Ordinaries and the Standard and Poor's Australian Securities Exchange 200 index (S&P/ASX 200). The All Ords is the older of the two and tracks the 500 largest companies on the Aussie share market weighted by market capitalisation, while the ASX/S&P 200 measures Australia's top 200 companies by market capitalisation.

The S&P/ASX 200 is of most interest to the investment world, and is usually what people refer to if they spit out the latest market level. In addition, index-linked funds typically track the S&P/ASX 200.

Here's a list of indices here and abroad you should know:

Australia

S&P/ASX 200: Australia's most cited market index. It's made up of the 200 largest Aussie stocks.

All Ordinaries: 500 largest Aussie companies by market size.

International

S&P 500: The 500 largest companies listed on US exchanges, about 80% of the full US market value.

Dow Jones: 30 blue-chip companies listed on US exchanges.

VIX: Measures the volatility of the S&P 500.

FTSE 100: The 100 largest companies on the London Stock Exchange.

Nikkei 225: Tracks the performance of 225 large companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

Nasdaq Composite: a collection of stocks listed on the US Nasdaq. It's heavily weighted towards tech stocks.

Dax: Blue chip index made up of 30 large companies listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange.

Heng Seng: Follows the 50 largest companies on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong.

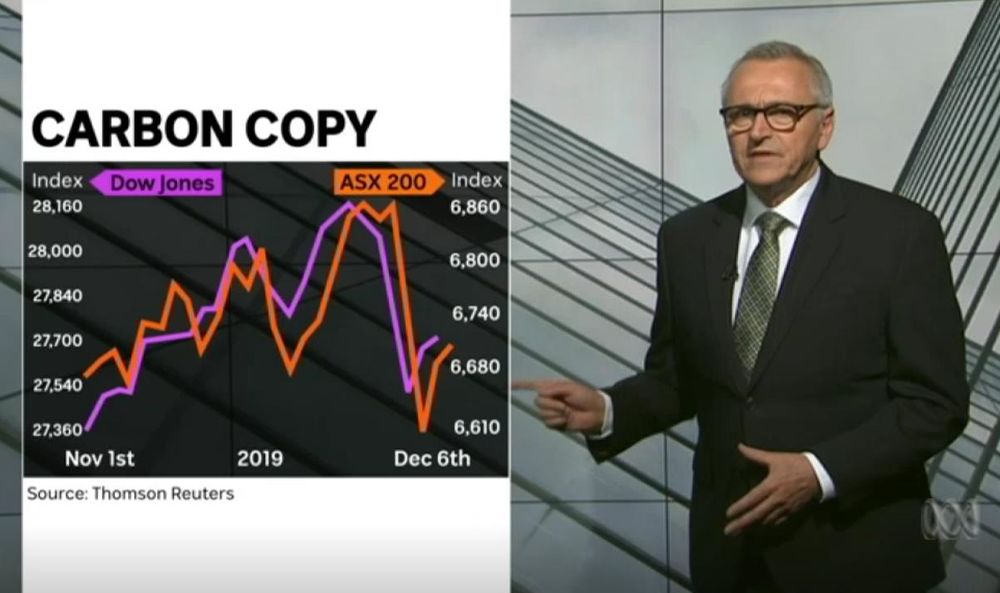

Copycat

The Australian stockmarket is hugely influenced by what happens overseas, a function of globalisation and the relatively small size of our economy. If US markets dive during the overnight session, chances are ours will follow suit come morning.

Similarly, if the Chinese economy takes a turn for the worse, our resource sector (which makes up about half the market) will likely get shaky knees over fear its number one customer will buy less of the stuff we dig up from the ground.

The US-China trade war is a good example. China is our mining industry's biggest customer, while the US is the beating heart of the global economy, so bad news for them usually means bad news for our miners.

Of course, it's not all about what happens overseas. Domestic events such as interest rate changes and the release of economic indicators also move market sentiment.

Announcements

The market moves up and down in large part because of company announcements. If a company makes an announcement that investors think could affect future earnings, they'll buy or offload shares accordingly.

This is more the case for speculative investors than for buy and hold investors like Warren Buffett and the experts we typically hear from at Money.

Public companies are required by law to announce anything that a reasonable person would assume affects the share price. All ASX announcements can be found here.

The same goes for economic or sector data. Think of them as symptoms of overall health - if the symptoms are bad, investors get anxious about the future.

Gold

Gold has always held a special place in our hearts and minds. It also holds a special place in finance.

The price of gold has historically been negatively correlated with stocks because it's seen as a safe place to store wealth when the stockmarket's skittish. So, when stocks go down gold goes up, and vice versa. In this way, it's served as a measure of investor sentiment.

This has changed recently, though. Gold and stocks have both been on the up. This doesn't mean gold is now correlated to stocks, but rather that it's not correlated to anything. This doesn't make it a bad or safe investment, but it does mean it's lost some potency for now as a barometer of market sentiment.

Bonds

Like gold, bonds are a safe place to store wealth. Also like gold, they're a key economic indicator.

The movement of yields up and down is in large part a reflection of market optimism. If market optimism sinks, people flock to bonds because they're deemed a safer place to store wealth than equities.

If investors think the market will head upwards, then they're more likely to leave safe assets like bonds and instead invest in stocks.

Investors buy bonds from issuers in exchange for regular coupon payments (which you can think of as the interest or yield of the bond). They're then held for a set period of time, after which the investor returns the face value of the bond to the issuer.

You'll often hear finance newsreaders note how bond yields have gone up or down. This is due to the sale and purchase of bonds in the secondary market.

If people are willing to pay more or less than the face value of the bond, the yield will go proportionately up or down in the opposite direction. In other words, more demand for bonds means yields go down, and less demand means yields go up.

Bond prices are also affected by interest rates, inflation, and credit ratings.

Exchange rates

Australia has a floating exchange rate, which moves up and down based on the exchange price of currency pairs. So if the Aussie dollar is trading at 70 US cents and you convert, say, $1000 from Aussie dollars to US dollars for spending during an overseas holiday, you'll have $700 to spend while you're there.

Exchange rates are exceptionally difficult to predict, which is one of the reasons why speculating on them is deemed so risky. Interest rates, growth rates, confidence, and relative inflation all influence them.

A low or falling currency is not necessarily a bad thing. In general, strong currencies favour countries that are net importers because overseas goods are cheaper to buy, while weaker currencies favour countries that are net exporters because it raises the competitiveness of their goods and services.

At last count, Australia was a net exporter, with a current account surplus of $7.86 billion - so a weaker Aussie dollar is a good thing. Like most things in life, though, too far one way or the other isn't a great thing.

And of course, if you plan to travel or buy something from overseas, a stronger dollar is definitely what you want.

Get stories like this in our newsletters.